Children’s Minnesota neurosurgeon, Dr. Kyle Halvorson, reviews guidelines for assessing and treating TBIs in children.

Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) are the leading cause of death and disability among children and adolescents in the U.S. In fact, it’s estimated that 20% of the 35,000 children who experience a severe TBI in the U.S. will die because of their injuries. Among survivors, 50% will experience poor neurological outcomes six months post-injury.

Not only do these statistics paint a startling picture of the reality of TBI among children, but they also highlight the importance of being prepared to assess, evaluate and treat TBIs in children.

Recently, Kyle Halvorson, MD, pediatric neurosurgeon at Children’s Minnesota, and Nathan Kreykes, MD, trauma medical director at Children’s Minnesota, led a video seminar focused on pediatric TBI. The session, “ABC’s of Pediatric Trauma: Pediatric Head Trauma: Assessment and Decision Making” was one video of our education series about pediatric trauma.

Below are key points on what Dr. Halvorson shared.

Listen to the entire (one-hour) free course here.

‘Kids are not small adults’

The first step in assessing and treating children with a TBI is to recognize that children are not small adults. This is a point Dr. Halvorson drives home in the video.

“Kids are not small adults,” he states. “Most of the literature and studies we have about treating and managing these types of brain injuries come from our adult colleagues. It’s important we recognize that what works for adults doesn’t always work for children because of physiological and physical differences.”

Dr. Halvorson points out the literature around pediatric head trauma is somewhat limited, possibly owing to the fact that brain injury mechanisms can vary widely among children.

“The mechanism of injuries we see in children can be very different,” he explains. “Brain injuries from a motor vehicle crash will be very different from an injury incurred during sports, a fall or a non-accidental head trauma, like shaken baby syndrome.”

However, there are recommended guidelines local hospitals and trauma teams can follow to help reduce the risk of secondary injury caused by TBI.

Understanding intracranial pressures changes

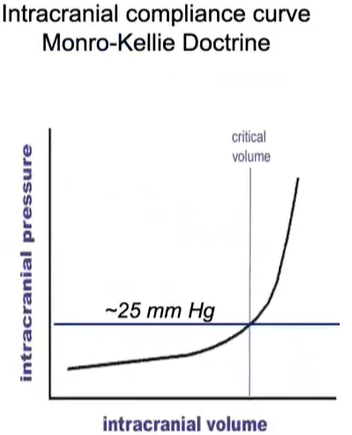

The best place to start is understanding how and when intracranial pressure (ICP) creates a serious threat to the health, safety and positive outcomes in children recovering from a brain injury.

“Our brains automatically regulate the equilibrium of brain tissue, blood volume and cerebral spinal fluid,” Dr. Halvorson explains. “We can all accommodate small changes in intracranial pressure when blood volume is in flux, but when we go beyond a few millimeters and have more intracranial volume, ICP goes up dramatically. When you see that rise, that is when you start to see problems.”

In TBI, the increased blood in the brain can quickly (and suddenly) lead to an elevated ICP.

According to Dr. Halvorson and his colleagues, an ICP of 15 mm Hg is the right target to start treating children for brain injury.

Signs of elevated ICP

Many of the signs of an elevated ICP are those that you would expect – loss of consciousness, vomiting and disorientation. Dr. Halvorson points out signs for specific age groups as well.

Signs of elevated ICP in infants

- Irritability.

- Tension of the fontanel.

- Disjunction of skull sutures.

- Increased skull growth.

- “Sunset eyes.”

Signs in children

- Postural headache.

- Diplopia.

- Papillary edema.

- Irritable, angry.

- Vomiting.

Late manifestations of ICP

- Depressed level of consciousness.

- Repeated vomiting.

- Stiff neck (axial brain compression).

- Cushing’s Triad.

- Strabismus.

- Coma.

Acute management strategies for intracranial pressure

Dr. Halvorson shares the basic tenets of treating elevated ICPs.

- Prevent hypotension by managing blood pressure with early and aggressive fluid resuscitation and early intervention of vasoactive medications.

Dr. Halvorson reminds physicians that hypertension with a brain injury is a neuroprotective mechanism, and it shouldn’t be aggressively lowered.

- Prevent hypoxemia and hypercarbia with early airway placement.

- Prevent anemia and blood loss with early transfusion, if necessary.

- Sedation can help reduce blood flow and oxygen requirements. This must be carefully managed.

- Prevent seizures with seizure prophylaxis and EEG monitoring.

- Prevent fevers, which are associated with secondary brain damage. (Only consider hypothermia for severe refractory. It is no longer supported as early line therapy.)

“The bottom line of treating traumatic brain injuries is to correct all the physiological derangements as quickly as possible,” Dr. Halvorson clearly states. “Research has shown that those who have survived TBI had hypotension and hypoxia treated early.”

A note on osmolar therapies

Hyperosmolar therapies have been a key approach to treating ICP after a TBI. Historically, mannitol was used to help reduce cerebral edema. Today, neurosurgeons are moving away from mannitol and toward hypertonic saline. Dr. Halvorson notes that hypertonics are easier to manage and tend to work better.

Collaboration saves lives

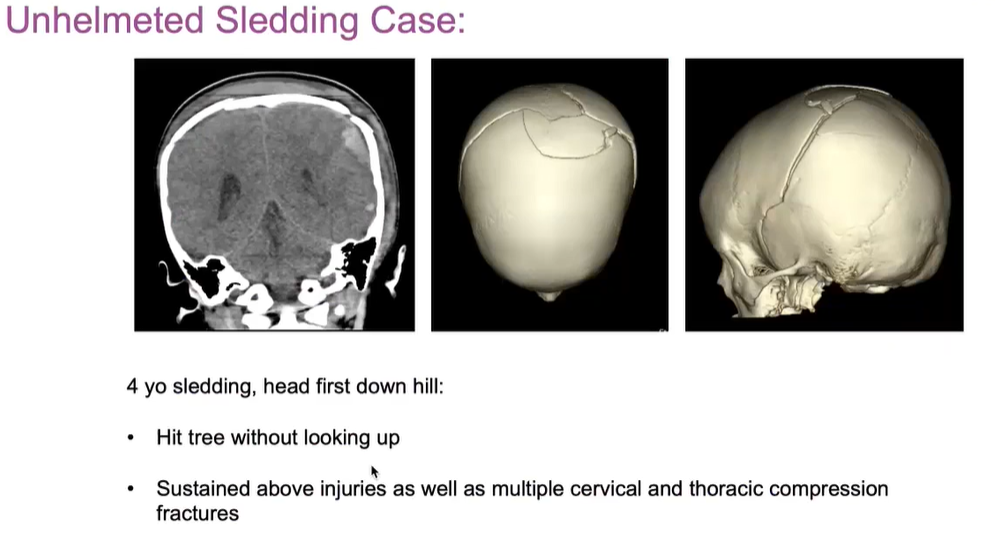

At the heart of effectively treating traumatic brain injuries and saving lives is working together across hospitals. That was clear in one recent case study, in which a 4-year-old sustained an extensive, complex skull fracture after sledding headfirst into a tree.

“The EMTs on the scene did an excellent job treating and preparing the child for transport to the hospital,” states Dr. Halvorson. “I was on the phone with the trauma physician at the local hospital as the child was rolled into his ER. That communication and dialogue was key so that, by the time the child arrived at Children’s Minnesota, we were able to take him straight into the operating room.”

The importance of onsite neurocritical care

Research has repeatedly shown that onsite care for brain trauma can improve outcomes and reduce morbidity and mortality from TBI. Dr. Halvorson points out research that has shown:

- Hypotension and hypoxia in the prehospital setting doubles the risk of mortality following TBI.

- Hypotension has been identified as the single most important parameter.

- Brain glucose levels can reach critically low levels particularly in pericontusional regions worsening energy levels.

- Hyperthermia leads to increased inflammatory response, blood flow and metabolic demands.

- Correction of derangements greatly ameliorates these effects in multiple models.

- Aggressive, early interventions should improve outcomes.

Guidelines for treating brain injuries at the scene include the ABCs (Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale), according to Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS)/Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS). Dr. Halvorson encourages responders and physicians to pay particular attention to:

- Hypercapnia – Aggressive bag-mask ventilation prior to rapid sequence intubation (RSI).

- Hypotension – Etomidate and rocuronium use for intubation.

- Hypoxemia – Even short duration is strictly avoided.

First responders and providers should also work to:

- Obtain secure IV access.

- Start volume expander IV therapy (to prevent hypotension).

- Initiate osmolar therapies.

Summary of evidence

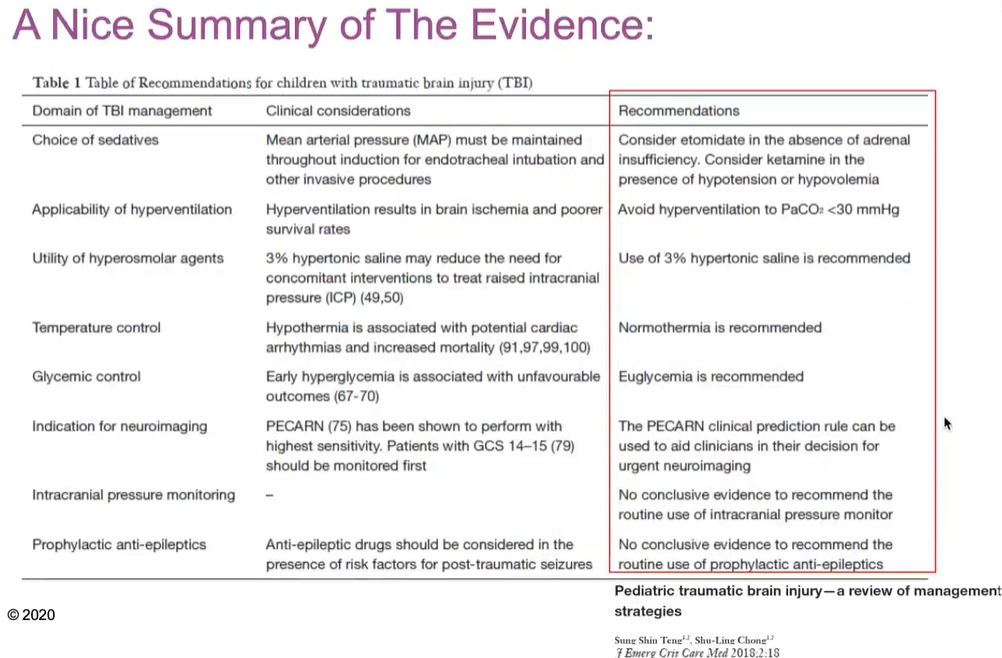

Dr. Halvorson notes at the beginning of his talk that guidelines can be tough for pediatric brain trauma because of the scope and variation of injuries. It should also be noted that parents aren’t typically willing to sign up their child for experimental care when they are in the emergency department with a TBI.

However, guidelines were reviewed and updated in 2019. They can be viewed in full here or through the Children’s Minnesota website.

Dr. Halvorson walks through these updated guidelines during the video and also shares a summary of recommendations.

Watch the full trauma series

The team at Children’s Minnesota is dedicated to sharing our knowledge and experience with physicians throughout our region. Our three-part trauma series can be viewed online. You can also watch the entire, hour-long Pediatric Head Trauma video.

Please note you will need to create a username and password to access the free recording.