Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS)

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) is a complex and rare heart condition. Children with HLHS have a combination of related heart problems.

A healthy heart is a strong, muscular pump that pushes blood through the circulatory system to carry oxygen and nutrients to the body. The heart has four chambers — two on the right and two on the left. Blood is pumped through these chambers and regulated by valves that open and close like tiny doors, so that blood can move in only one direction.

After its trip through the body to deliver oxygen, blood is a blue color because it’s no longer oxygen-rich. The blue blood returns to the heart through the right chambers and is pumped through the pulmonary artery into the lungs. In the lungs, it picks up more oxygen and becomes bright red. It then goes back through the pulmonary vein to the left chambers and is pumped through the aorta and out into the body again.

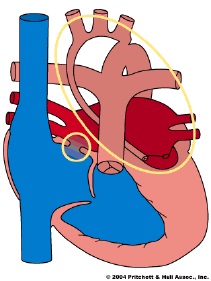

If your baby is born with HLHS, the chambers and arteries on the left side of the heart are small and underdeveloped with valves that don’t work properly. Since the left side can’t pump effectively, the right side of the heart must take on double the work and pump to both the lungs and the rest of the body.

A newborn baby with HLHS may appear to be well during the first hours or even days of life. However, a day or two after birth, the natural openings between the right and left sides of the heart close. That is normal, but in a baby with HLHS, it can be fatal because it leaves the overworked right side of the heart no way to pump blood to the body.

What causes HLHS?

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome occurs during the first eight weeks of fetal growth when the baby’s heart is developing. The cause is unknown. However, if your family has one child with HLHS, the risk of having another with the same condition is higher than the recurrence rate for other congenital heart defects. This may mean genetics play a role. It’s possible for a fetus to be diagnosed with HLHS through an ultrasound exam as early as the first trimester.

HLHS comprises 4-8% of all congenital heart defects. It occurs in up to four out of every 10,000 live births. HLHS appears slightly more often in boys than in girls. Beyond family history, there are no clear risk factors for it, and no known way to prevent it.

What are the signs and symptoms?

Usually, babies born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome are critically ill right away. Signs and symptoms vary, but may commonly include:

- Cyanosis: A blue (or gray) tone to the skin, lips, or nails

- Pale, cool or clammy skin

- Difficulty breathing

- Accelerated heart rate

- Fainting or loss of consciousness

- Poor feeding

- Cold hands and feet

- Lethargy

If the natural connections between the heart’s left and right sides are allowed to close naturally a day or two after birth, the child may go into shock. Symptoms of shock include:

- Dilated pupils; eyes that seem to stare blankly

- Slow and shallow (or very rapid) breathing

- A weak and accelerated pulse

- Pale, cool, and clammy skin

A baby in shock may be either conscious or unconscious. If you suspect your baby is in shock, dial 911 right away.

How is it diagnosed?

A clear diagnosis is the first step to treatment. Doctors can use ultrasound to diagnose HLHS before birth. If there is a concern for heart disease either by prenatal ultrasound or because of presenting symptoms, doctors may order an echocardiogram, which uses sound waves to make a moving image of the heart on a video screen.

It’s important to diagnosis HLHS before or shortly following birth so that a treatment plan can be developed as soon as possible. The postnatal management requires a life saving medication (prostaglandin) that is started immediately after birth to support blood flow to the vital organs. If HLHS is diagnosed before birth, doctors will recommend that the mother gives birth at a hospital with cardiac surgery capabilities. There is a rare subset of babies with HLHS who are profoundly sick at birth and require immediate resuscitation. For this reason, it is very important that any suspicion prenatally for a cardiac abnormality be followed-up with a fetal echocardiogram.

A pediatric cardiologist (a children’s heart doctor) can use several tests to confirm your child’s diagnosis. These tests may include:

- Chest X-ray: A beam of electromagnetic energy creates images on film that show the inside structures of your baby’s body.

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): This test produces a three-dimensional image of the heart so you’re your child’s doctors can examine blood flow and functioning of the heart as it is working.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG): This test, conducted by attaching patches with wires (electrodes) to your baby’s skin, records the heart’s electrical activity. It will show if there are abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias or dysrhythmias) and/or stress on the heart muscle.

- Echocardiogram (Echo): This test uses sound waves to make a moving image of the heart on a video screen. It is similar to an ultrasound, If your baby has HLHS, the echocardiogram may show a smaller than normal left ventricle and aorta, as well as a reversed blood flow. The echo can also identify any related heart defects.

- Cardiac catheterization: During this procedure, your doctor inserts a thin flexible tube (a catheter) into a blood vessel in the groin, then guides it up to the inside of the heart. A dye injected through the catheter makes the heart structures visible on x-ray pictures. The catheter also measures blood pressure and oxygen levels.

How is it treated?

Due to the advances in medical science in recent years, babies born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome today have a much improved outlook.

Once diagnosed, your child’s specific treatment may vary, depending on his or her individual needs. Your child will probably be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) or special care nursery and may be placed on oxygen or a ventilator to help with breathing. Intravenous (IV) medications may be given to assist heart and lung function and stop the two sides of the heart from closing naturally. Your baby’s doctor may also recommend an atrial septostomy, which is a procedure to create a helpful opening between the heart’s upper chambers.

For babies born with HLHS, there are two treatment options: a heart transplant, or far more commonly, a series of surgeries to reconstruct the heart to compensate for the otherwise-fatal defects. The procedures, which Children’s helped pioneer, are:

- A Norwood operation: Performed within two weeks of birth, this surgery reconstructs and reconnects the aorta and the lower right chamber of the heart. Your baby’s skin will still have a blue tone, as oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood continue to mix in the heart.

- A bi-directional Glenn or hemi-Fontan: Performed between four to six months of age, this surgery reduces the burden on the heart’s right chamber. After the surgery, blood with more healthy oxygen will be pumped to organs and tissues throughout the body.

- The Fontan procedure: Performed between 18 months and three years of age, this surgery stops oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood from mixing in the heart. After the surgery, your child’s skin will no longer look blue.

The second surgical option is a complete heart transplant. Babies with HLHS may need special medications while waiting for a donor heart to become available.

After surgery or a transplant, your baby will need lifelong follow-up care with a heart doctor who specializes in congenital heart disease. Some medication may be necessary to regulate heart function. If your baby receives a heart transplant, he or she will need to take anti-rejection medication for the rest of his or her life to combat rejection of the new heart.

Later in life, children who have had either treatment for hypoplastic left heart syndrome sometimes tire easily from exercise, experience heart rhythm abnormalities or blood clots, or have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).Your child’s cardiologist may also recommend that your child limit physical activity and take antibiotics before dental procedures to prevent infections.

What are the long-term care needs for babies and kids with HLHS?

Children with congenital heart diseases such as HLHS typically remain in the care of a pediatric cardiologist for the duration of their childhood through early adulthood. Depending on each individual’s clinical situation, medications, catheterizations, and occasionally additional surgery is necessary after the third stage of palliation. There is surveillance throughout life to assess for cardiac muscle dysfunction and laboratory studies obtained at various intervals to assess liver function (the liver is “congested” in patients with Fontan circulation). Some patients will require cardiac transplantation in childhood or adulthood if the heart muscle is very weak despite medical therapies or if the Fontan circulation fails. In adulthood, patients with HLHS should be seen regularly at centers with experts in adult congenital heart disease.

Once treated for HLHS, what does the future look like?

After treatment for Hypoplastic left heart syndrome, most children can be active like others their age, but with a few special considerations. Every child with HLHS has a unique case and requires specialized treatment and care. Sometimes, but not always, children with HLHS may be more likely to:

- Tire easily from exercise

- Not tolerate extreme temperatures or altitudes well

- Experience heart rhythm abnormalities or blood clots

- Develop attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

About treatment for hypoplastic left heart syndrome at Children’s

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is treated through Children’s Cardiovascular program one of the largest and oldest pediatric cardiovascular programs in the region. Team members consistently achieve treatment results that are among the best in the nation. Each year, care is provided for thousands of the region’s sickest children with heart conditions, including fetuses, newborns, infants, children, adolescents, and adult, long-term patients with pediatric cardiovascular conditions.

Contact us

For more information, please call Children’s Heart Clinic at 1-800-938-0301.

Heart with hypoplastic left heart syndrome

(From Pritchet & Hull Assoc., Inc.)

Resources

- WCCO-TV Kylie’s Kids: Meet Ben: Ben underwent three surgeries at Children’s Minnesota to improve his heart function, allowing him to lead the active lifestyle of a typical five-year-old boy.

- Jamestown Sun: ‘Born with half a heart’: Ian Trautman spent his first month of life in the Children’s Minnesota neonatal intensive care unit awaiting his first open heart surgery for HLHS. Read more about his story and congenital heart disease.