Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV)

What Is Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV)?

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) is a heart defect where the aorta connects to the heart in the wrong place. DORV is a congenital heart defect, which means a baby who has it is born with it.

Usually, the aorta is attached to the left ventricle (pumping chamber), and the pulmonary artery is attached to the right ventricle. In babies with DORV, both vessels are attached to the right ventricle.

Along with the misplaced aorta, babies with DORV also have a ventricular septal defect (VSD), a hole in the wall that normally separates the left and right ventricles.

Babies born with DORV almost always show signs of the problem within a few days of birth. Surgery is needed to correct the problem.

What Happens in Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV)?

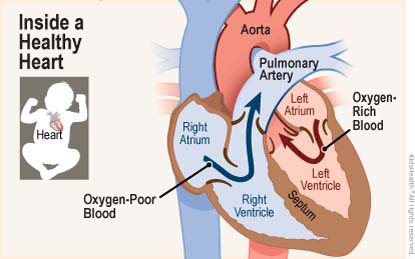

The normal heart has two main jobs:

- It receives oxygen-poor blood back from the body and pumps it to the lungs to pick up a fresh supply of oxygen, making the blood oxygen-rich again.

- It pumps oxygen-rich blood out to the body.

The heart does these jobs using two blood flow loops:

- The right atrium receives oxygen-poor blood from the body and passes it to the right ventricle. The right ventricle then sends the oxygen-poor blood to the lungs through the pulmonary artery.

- The left atrium gets oxygen-rich blood from the lungs, then passes it to the left ventricle (pumping chamber), which sends the oxygen-rich blood to the body through the aorta.

After the blood becomes oxygen-rich in the lungs, it returns to the left ventricle, ready for another loop through the body.

When a baby's heart has DORV:

- Oxygen-rich blood from the lungs returns to the left ventricle, but can't leave through the aorta as it does in a normal heart.

- The only way oxygen-rich blood can leave the left ventricle is to pass through the VSD into the right ventricle. There, it mixes with the oxygen-poor blood returning from the body.

With each heartbeat, the right ventricle squeezes the mixed blood out to the lungs through its normal outlet (the pulmonary artery) and out to the body through the misplaced aorta. The mixing of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood makes the heart with DORV work harder than a normal heart usually does.

The position and size of the VSD and the positions of the pulmonary artery and aorta are different for each baby. So some babies with DORV have more severe symptoms than others.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV)?

Within a few days of birth, a newborn with DORV usually will show these signs:

- breathing fast or hard

- pale or bluish skin

- sweating

- poor feeding with little weight gain

- sleepiness

What Causes Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV)?

DORV is due to an error in the way the heart forms very early in pregnancy. Why this happens is unknown. It isn't caused by anything a mother did or didn't do during her pregnancy. Doctors and scientists have not yet found a way to prevent DORV.

Who Gets Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV)?

In most cases, DORV happens with no known cause. Babies with certain genetic conditions — such as trisomy 13, trisomy 18, or DiGeorge syndrome (22q11.2 deletion) — are more at risk for DORV.

How Is Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV) Diagnosed?

DORV sometimes is seen on ultrasound scans before birth. A fetal echocardiogram (a more detailed ultrasound scan) may provide more information and guide the delivery team's preparations.

If the diagnosis is made after the birth, it's the baby's skin color and breathing problems that indicate a problem. Doctors listening to the baby's heartbeat may hear an abnormal sound (a murmur) and use these tests to look at the baby's heart:

- pulse oximetry: measurement of the oxygen in blood using a light at a fingertip or toe

- chest X-ray

- electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG): a recording of the heart's electrical activity

- echocardiogram: ultrasound images and videos of the heart

- cardiac MRI or CT scan

In some cases, a cardiac catheterization is needed.

Babies with DORV often have more than one heart problem. So while doctors check to see how the outlet vessels and VSD are arranged, they will also look for other problems.

How Is Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV) Treated?

Surgery is needed to correct DORV. Medicines might help the heart work better, but a baby with DORV cannot get better for long without surgery.

The main types of surgery used are intraventricular repair, arterial switch, and single ventricle pathway. More than one surgery might be needed to get the heart working as well as possible.

Intraventricular Repair

This surgery uses a patch to make a tunnel from the VSD to the aorta. Then, when the heart contracts, the oxygen-rich blood in the left ventricle flows through the VSD into the aorta. After the repair, there is no longer mixing of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood in the right ventricle.

Arterial Switch

The arterial switch repair moves the aorta from the right ventricle to the left ventricle. The VSD is closed to keep oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood from mixing in the ventricles.

Single Ventricle Pathway

In some cases many surgical steps (called the single ventricle pathway) are needed to balance blood flow in a baby with DORV:

- At age 2 weeks or younger: A Blalock-Taussig (BT) shunt redirects some of the left ventricle's output from the body to the lungs. – OR – If the blood flow to the lungs is too high, as can happen with a large VSD, a band around the pulmonary artery lessens the flow to prevent damage.

- At age 4‒6 months: The Glenn procedure allows blood returning from the upper part of the body to flow directly to the lungs. The BT shunt is removed at the same time.

- At age 1.5‒3 years: The Fontan procedure channels blood from the lower half of the body to the lungs so the heart pumps oxygen-rich blood to the body only. Blood returning from the body flows to the lungs before passing through the heart.

In very rare cases, surgical repair isn't possible and a heart transplant may be recommended.

What Else Should I Know?

Extra pressure on blood going to the lungs of babies with DORV can damage the lungs' blood vessels and lead to heart failure. Because problems like this and others are likely, infants with surgically corrected DORV must continue to see a cardiologist (a doctor who treats heart problems) through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

Note: All information is for educational purposes only. For specific medical advice, diagnoses, and treatment, consult your doctor.

© 1995-2024 KidsHealth ® All rights reserved. Images provided by iStock, Getty Images, Corbis, Veer, Science Photo Library, Science Source Images, Shutterstock, and Clipart.com