Tricuspid Atresia

What Is Tricuspid Atresia?

Tricuspid atresia is a congenital heart defect (this means that a baby who has it is born with it). It happens when the heart's tricuspid valve does not develop. This means that blood can't flow from the heart's right atrium (upper receiving chamber) to the right ventricle (lower pumping chamber) as it should.

A baby born with tricuspid atresia often has serious symptoms soon after birth because blood flow to the lungs is much less than normal.

What Happens In Tricuspid Atresia?

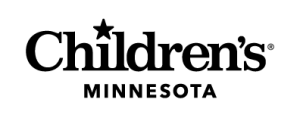

In a normal heart, the tricuspid valve lets blood flow from the right atrium into the right ventricle. When the right ventricle squeezes to pump blood to the lungs, the tricuspid valve closes. This keeps blood from flowing back into the right atrium.

The right side of the heart (the right atrium and the right ventricle) gets oxygen-poor blood from the body and pumps it to the lungs. Then, the lungs add fresh oxygen to the blood. The blood, now full of oxygen, returns to the left side of the heart. The left atrium gets the oxygen-rich blood and passes it to the left ventricle, which then pumps it out to the body.

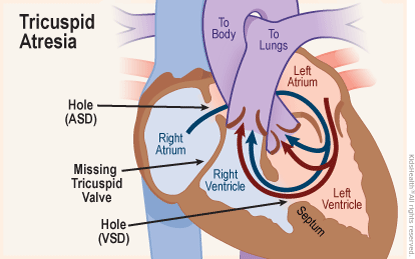

In a heart with tricuspid atresia, solid tissue sits between the right atrium and the right ventricle. Because blood in the right atrium can't move through the tricuspid valve, the wall separating the right and left sides of the heart does not form completely.

In most babies with tricuspid atresia, the heart has two holes:

- an atrial septal defect (ASD), which is a hole between the right atrium and the left atrium

- a ventricular septal defect (VSD), which is a hole between the right ventricle and left ventricle

Oxygen-poor blood received by the right atrium can only flow by the atrial septal defect (ASD). The oxygen-poor blood passes through the ASD into the left atrium, where it mixes with oxygen-rich blood. The left atrium passes the mixed blood to the left ventricle. The left ventricle pumps most of the mixed blood to the body, but some pushes through the ventricular septal defect (VSD) and the right ventricle to the lungs.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of Tricuspid Atresia?

Soon after birth, a newborn with tricuspid atresia usually will:

- have bluish skin (cyanosis)

- breathe fast

- have problems feeding

- get tired quickly when feeding

- be less active than most babies

What Causes Tricuspid Atresia?

Tricuspid atresia happens when the heart forms very early in pregnancy. No one knows why the the valve doesn't grow normally.

Who Gets Tricuspid Atresia?

A baby is more likely to have tricuspid atresia if:

- the baby has Down syndrome (trisomy 21)

- either parent has a congenital heart defect

- the mother had a rubella (German measles) infection or other viral infection during pregnancy

- the mother has poorly controlled diabetes or lupus (an autoimmune disease)

- the mother uses certain anti-acne or anti-seizure medicines during pregnancy

But, having one or more risk factors doesn't mean that a baby will have tricuspid atresia. Tricuspid atresia can happen without any risk factors.

How Is Tricuspid Atresia Diagnosed?

Tricuspid atresia sometimes is seen on ultrasound scans before birth. A fetal echocardiogram (a more detailed ultrasound study of the unborn baby's heart) can give more information and help the delivery team plan treatment.

A screening usually is done on all newborns right after birth using a light on a fingertip or toe. If tricuspid atresia isn't found before birth, this test will show that the baby's blood is not carrying as much oxygen as expected. The delivery team will then do other tests to find the problem and help plan treatment.

The tests may include:

- pulse oximeter monitoring

- a chest X-ray

- electrocardiogram (also called ECG or EKG, a recording of the heart's electrical activity)

- echocardiogram (ultrasound images and videos of the heart)

How Is Tricuspid Atresia Treated?

Treatment for tricuspid atresia combines medicine, surgery, and cardiac catheterization to improve the flow of blood to the lungs. Replacing the tricuspid valve does not help because the right ventricle is not large enough to pump blood well.

Medicines

A medicine called prostaglandin E1 helps keep the ductus arteriosus (often just called "the ductus") open. The ductus arteriosus is a normal blood vessel that connects two major arteries — the aorta and the pulmonary artery — that carry blood away from the heart. Keeping the ductus open in babies with tricuspid atresia improves the flow of blood to the lungs.

Surgery

These surgical steps (called the single ventricle pathway) can improve blood flow to the lungs in a baby with tricuspid atresia:

- At age 2 weeks or less: A Blalock-Taussig (BT) shunt redirects some of the left ventricle's output from the body to the lungs. – OR - If the blood flow to the lungs is too high, as can happen with a large ventricular septal defect, a band around the pulmonary artery lessens the flow to prevent damage.

- At age 4‒6 months: The Glenn procedure allows blood returning from the upper part of the body to flow directly to the lungs. The BT shunt is removed at the same time.

- At age 1.5‒3 years: The Fontan procedure channels blood from the lower half of the body to the lungs so the heart pumps oxygen-rich blood to the body only. Blood returning from the body flows to the lungs before passing through the heart.

Doctors decide which steps to take based on what they learn from all the tests.

Cardiac Catheterization

Cardiac catheterization can make or enlarge openings in the wall between the two atria and between the two ventricles. It also can be used to place a stent (mesh tube) in the ductus to keep it open.

Looking Ahead

Treatments for tricuspid atresia improve the baby's condition, but can't make the heart work like one without a defect. A child born with tricuspid atresia will regularly see a cardiologist (a doctor who treats heart problems) throughout childhood and as an adult.

Note: All information is for educational purposes only. For specific medical advice, diagnoses, and treatment, consult your doctor.

© 1995-2024 KidsHealth ® All rights reserved. Images provided by iStock, Getty Images, Corbis, Veer, Science Photo Library, Science Source Images, Shutterstock, and Clipart.com