Aortic Stenosis

What Is Aortic Stenosis?

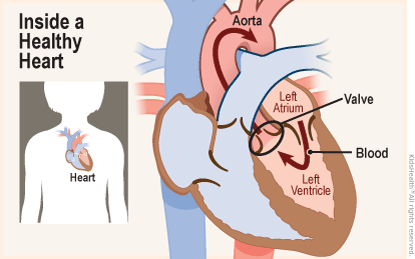

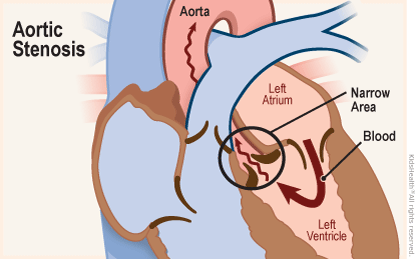

Aortic stenosis is when the aortic valve (the valve between the left ventricle and the aorta) is too small, narrow, or stiff.

Symptoms of aortic stenosis depend on how small the narrowing of the valve is. Many people have no symptoms at all, and others have only mild symptoms. Mild cases may not need any treatment. But kids with more severe aortic stenosis will need surgery to fix the aortic valve so that blood flows properly through the body.

What Happens in Aortic Stenosis?

The aortic valve and pulmonary valves control the flow of blood as it leaves the heart and keep it flowing forward. They open to let blood move ahead, then quickly close to keep it from flowing backward.

In aortic stenosis (ay-OR-tik stuh-NO-sis), the aortic valve is too small and narrow. It can't open all the way. This makes the heart work harder to push blood across the abnormal valve. Over time, this added stress can weaken the heart.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of Aortic Stenosis?

Many people with aortic stenosis have no symptoms. Others have mild symptoms that usually don't become bothersome.

Infants with more serious aortic stenosis may show signs of heart failure, such as trouble gaining weight, problems with feeding, and breathing problems that develop soon after birth.

People with severe aortic stenosis may have chest pain, be short of breath, and feel tired or dizzy. These symptoms may be worse during activities or exercise.

What Causes Aortic Stenosis?

In children, aortic stenosis happens when part of a baby's heart doesn't develop the way it should during pregnancy. Doctors don't know why this happens, but it isn't caused by anything a mother did or didn't do during her pregnancy, so could not have been prevented.

Aortic stenosis usually affects older adults, but some babies are born with it. The defect is more common in boys.

How Is Aortic Stenosis Diagnosed?

Doctors often can identify aortic stenosis before birth. This lets babies born with severe problems be treated right away.

A fetal echocardiogram (also called a fetal echo) is a type of test that can help diagnose heart defects. A fetal echo uses a detailed heart ultrasound study to see how the baby's heart looks and works while still in the mother's womb.

If the problem wasn't found before birth, infants and older kids who have a suspected heart problem get an echocardiogram. Less commonly, a heart catheterization may be done if the diagnosis isn't clear. In a catheterization, a doctor inserts a catheter (a thin, flexible plastic tube) into an artery and vein that lead to the heart.

How Is Aortic Stenosis Treated?

Mild cases of aortic stenosis may not need treatment. Medicines sometimes can treat symptoms, but in severe cases the valve will need to be fixed or replaced.

Several types of procedures can repair or replace the aortic valve. Young children with a severe problem may undergo a balloon valvuloplasty during heart catheterization. With this procedure, a doctor threads an unopened balloon through the aortic valve and inflates it to open the valve.

Valve replacement involves using an artificial valve or a valve from a donor to replace the child's abnormal valve.

To decide what type of treatment to use, doctors consider:

- the location and amount of the narrowing

- the child's age and size

- how well the other valves in the heart are working

- whether the child has had previous heart surgery

- whether the child has other medical conditions

What Else Should I Know?

The biggest challenge for kids with aortic stenosis is that it can come back after treatment. This can happen for different reasons, including scar tissue that forms after a procedure or a valve replacement that doesn't grow as kids get bigger. So some kids might need several operations.

Because aortic stenosis can be a lifelong condition, kids who have the defect will need regular checkups with a cardiologist (a doctor who specializes in treating heart problems) to make sure that the narrowing isn't getting worse.

Many children won't need specific medical treatment, and those who do usually can enjoy most regular activities after their recovery. Kids and teens with moderate or severe aortic stenosis should talk with their cardiologist before playing competitive sports or being very physically active.

If your child has a heart condition, the care team is there to support you and your child. Be sure to ask when you have questions.

You also can find more information and support online at:

Note: All information is for educational purposes only. For specific medical advice, diagnoses, and treatment, consult your doctor.

© 1995-2024 KidsHealth ® All rights reserved. Images provided by iStock, Getty Images, Corbis, Veer, Science Photo Library, Science Source Images, Shutterstock, and Clipart.com