How is intestinal atresia diagnosed?

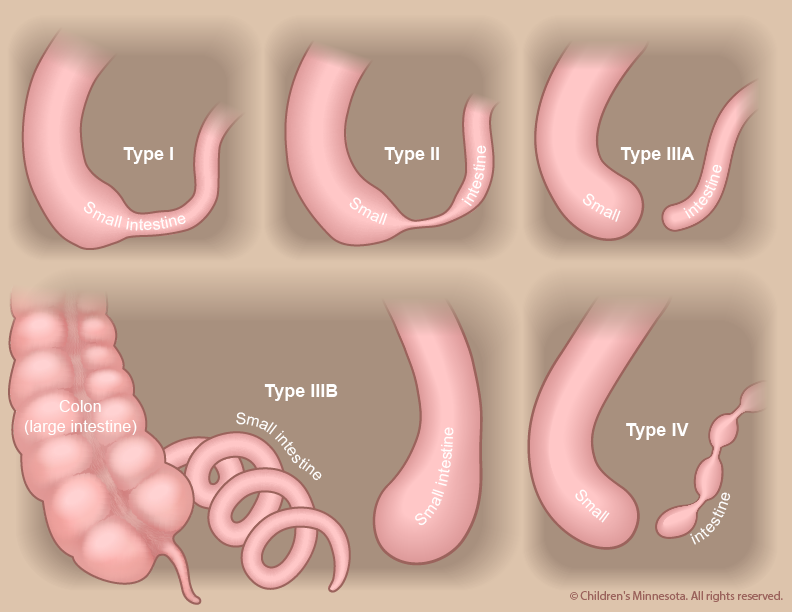

A routine ultrasound image taken during pregnancy may show that the baby has a dilated (distended) intestine or, more rarely, that the uterus contains excessive amounts of amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios). Both are potential indicators of intestinal atresia. If these signs are present, a more detailed ultrasound will be done to see if the condition can be confirmed. Most cases of intestinal stenosis and type I atresia are not detected prenatally, but the other classes of intestinal atresia (types II, III and IV) can usually be diagnosed by ultrasound during the third trimester.

How is intestinal atresia managed before birth?

The prenatal management of babies with intestinal atresia starts with acquiring as much information about the condition as early as possible. The information is critical because children with certain classifications of intestinal atresia — types III and IV — have a higher risk of preterm birth. They are also more likely to have shortened intestines. To gather the information, we will use a non-invasive procedure known as high-resolution fetal ultrasonography. In some cases, we may also recommend another non-invasive procedure, fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

What is high-resolution fetal ultrasonography?

High-resolution fetal ultrasonography is a non-invasive test performed by one of our ultrasound specialists. The test uses reflected sound waves to create images of the baby within the womb. We will use ultrasonography to follow the development of your baby’s intestinal tract — and other internal organs — throughout your pregnancy. We will look for signs of atresia, particularly a dilated intestine. We will also look for signs of polyhydramnios, which may raise the risk of an early delivery.

What is fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)?

Fetal MRI is another non-invasive test. It uses a large magnet, pulses of radio waves and a computer to create detailed images of your baby’s organs and other structures while in the womb. This procedure involves both mom and baby being scanned while partially inside our MRI machine. The test is a bit loud, but it takes only about 30 minutes and is not uncomfortable.

What happens after my evaluation is complete?

After we have gathered all the anatomic and diagnostic information from the tests, our full team will meet with you to discuss the results. Intestinal atresia cannot be definitively treated before a child is born. We will, however, take an active approach to managing the condition during your pregnancy. We will monitor both mother and baby very carefully, looking for any potential complications that might lead to premature delivery. One of those potential complications is polyhydramnios, which can occur when the atresia (blockage) makes it difficult for the baby to swallow. If this happens, we will watch closely for signs of preterm labor and/or symptoms in the mother related to the increased uterine size and pressure.

Occasionally, an amnioreduction is performed. This procedure, which is similar to an amniocentesis, removes some of the excess amniotic fluid and alleviates any symptoms the mother may be experiencing. The procedure is straightforward and can be done in our clinic. It requires numbing the skin on the mother’s belly and placing a small needle through the abdomen and into the amniotic sac to withdraw excess fluid.

How is intestinal atresia treated after birth?

Infants with intestinal atresia can be delivered vaginally. Our goal will be to have your baby’s birth occur as near to your due date as possible. Your baby will be born at The Mother Baby Center at Abbott Northwestern and Children’s Minnesota in Minneapolis or at The Mother Baby Center at United and Children’s Minnesota in St. Paul. Children’s Minnesota is one of only a few centers nationwide with a birth center located within the hospital complex. This means that your baby will be born just a few feet down the hall from our newborn intensive care unit (NICU). Also, many of the physicians you have already met will be present during or immediately after your baby’s birth to help care for your baby right away.

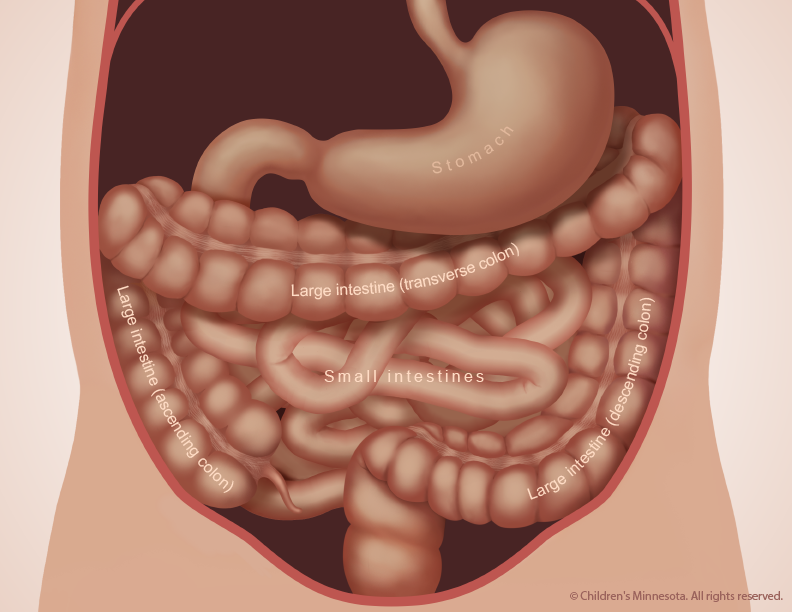

Your baby will need specialized medical care after birth and will therefore be taken to our NICU. Most babies with intestinal atresia are comfortable breathing on their own, but your baby will be unable to nurse or take a bottle and will be fed nutrients intravenously instead. Because your child’s intestine is blocked by the atresia, a thin flexible tube will be inserted into your baby’s stomach through either the nose or mouth. This tube will be used to suck out any air or fluid that collects in the child’s stomach.

Our goal will be to make a definitive diagnosis of intestinal atresia as quickly as possible. That diagnosis can be made with a simple x-ray, done soon after birth.

When will my baby have an operation?

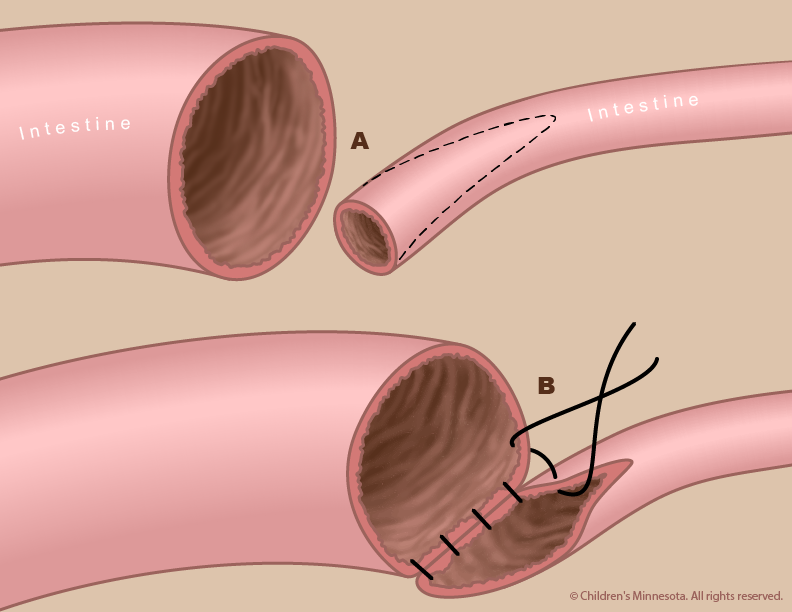

Treatment for intestinal atresia requires an operation to remove the blockage (atresia) and repair the affected part of the intestine. The surgery is not considered an emergency, and is typically done when the baby is two or three days old.

The exact nature of your baby’s surgery will depend on the specific defects in your baby’s intestine. In most cases, the surgeon removes the atresia and then repairs the intestine by sewing the two ends together.

The surgery is done under general anesthesia. Afterward, your baby will be returned to the NICU. For several days, your baby may need a machine (ventilator) to help with breathing.